MGNREGA payment woes: bad to worse?

To check corruption under the MGNREGA, the Centre is routing funds through banks and POs. But this has resulted in delayed payment and loss of faith in the system among people. Pradeep Baisakh argues the case for the earlier cash payment system.

17 July 2010 - “Apply for work, get work, and get paid on time”. This is how the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) took off in February 2006. Various instruments like muster rolls and job cards were designed to keep the payment process transparent. However, it was soon realised that a good chunk of money was being siphoned off by officials and implementers.

Consequently, in a circular dated 21 January 2008, Ministry of Rural Development instructed the state governments that “opening of bank and post office accounts of all the NREGA beneficiaries must be done before April 1, 2008”. The Government’s primary concern was to rule out the possibility of officials/implementers/middlemen ‘taking a cut’ while disbursing the wages. All the states have officially adopted in the new system barring probably Tamil Nadu.

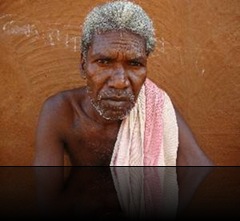

Papatu Devi and Koshila Devi of Chhatrapur block of Palamu district in Jharkhand are still waiting for the wages for the work they did four months ago. Pic: Pradeep Baisakh.

However, subsequent surveys in Odisha (2007) and Jharkhand (2008), and observations from many other states like West Bengal highlight delay in delivery of wages as the most frustrating reason for people to lose faith in the scheme. By April 25, 2010, there was delay in delivering wages amounting to Rs 1,355 crores (www.nrega.nic.in), of which, about Rs 136 crores were paid after 90 days of delay, Rs 156 crores in between 60-90 days, Rs 466 crores between 30-60 days, and Rs 596 crores between 15-30 days of delay.

The total wage payment (unskilled) made during 2009-10 was about Rs 25,000 crores. Consequently, 54 percent of the wages did not reach the labour force on time, i.e., 15 days. That delayed wages is an issue too conspicuous to go amiss was further substantiated with Prime Minister Manmohan Singh and UPA Chairperson Sonia Gandhi admitting it just as much.

Loopholes in the new system

The system works differently across states. In Rajasthan and Jharkhand, though the system of institutional payment has been put in place at least at the policy level, delays have been reported nevertheless. “In Chhattisgarh, it takes between one-and-a-half to two months to process payments,” says Gangaram Paikrai, a social activist.

In case of banks, although the process moves a bit faster, distance between villages and banks poses bottlenecks and exposes the system to many kinds of manipulation. For instance, the Utkal Gramya Bank (UGB) branch office is 15 km away from the Badabanki GP headquarters. Unaware of the bank transactions and schedules, villagers seek help from middlemen, mostly contractors, and pay for it. Frauds of this nature have come to light in Odisha and Jharkhand. Even in cases where the role of middlemen is limited, lack of knowledge about banking and overworked bank staff force the villagers to visit the banks at least 2-3 times to get what is rightfully theirs. This has been observed in Chhattisgarh, Odisha, and Jharkhand.

During a social audit conducted by the G B Pant Institute in Karon block of Deogarh in Odisha in October-November 2007 and in Jharkhand in November 2008, it was found out that the implementers resorted to corrupt ways to fleece villagers: forged signatures of the beneficiaries to withdraw money; contractors/middlemen accompanied the villagers to the bank while withdrawing the money and took a cut out of it. Another way of swindling was by obtaining the account-holders’ signatures on withdrawal forms on one pretext or the other and then withdrawing money without the knowledge of the latter.

Discussion with authorities in Badbanki GP, Tureikala block of Balangir district of Odisha, revealed that payment through POs takes about 26-30 days; of which, postal processing itself takes about 15-20 days as the cheque has to pass through the district PO and the sub-divisional PO before it is disbursed to labourers by the local PO. People, however, claim that they received wages though POs more than two months after the completion of one phase of work spread over 14 days.

People cannot escape corruption in POs either. Jawahar Mehta, a Jharkhand-based social activist, says, “In Garhwa district, people complained that they had to give the postmaster 2% of their earnings while withdrawing wages from the local branch.”

Gangaram Paikrai from Chhattisgarh says, "Post offices are often run by only one official. Naturally, it becomes very difficult to cope up with the task of payment under the MGNREGA.”

Old system vs. the new

Some studies suggest that the level of corruption in wage payment has gone down ever since the government started routing the funds through POs and banks. In their article “NREGA Wage Payments: Can We Bank on the Banks?”, Anindita Adhikari, Kartika Bhatia write drawing facts from their survey in Karchana and Shankargarh blocks in Allahabad district of Uttar Pradesh and Mander and Angara blocks of Ranchi district of Jharkhand that 76% of the sampled workers confirmed the accuracy of the bank records. This, by any standards, is a fair delivery of wages.

But somewhere down the line, the very intent of MGNREGA is getting defeated. Each new mode of payment comes with its own inherent drawbacks. For instance, in the previous cash payment system, muster rolls and job cards were necessary documents to monitor payments and they were easily accessed by the poor labourers. Similarly, the open system of payment by ‘roll call' of labourers was monitored by the community as was experimented in the Dungarpur (before the NREGA came into effect) and other areas of Rajasthan where Mazdoor Kishan Shakti Sangathan (MKSS) was at work.

Conversely, in the new system, documents are not easily accessible even by activists, let alone villagers in remote areas. It therefore weakens the community monitoring of wage payment of the scheme. The new system has rendered job cards meaningless and social audits, tedious. For instance, in Jharkhand, labourers come to know about the amount paid for the work done only when they receive the money from POs. In such cases, any underestimation of their work by junior engineers results in underpayment and the workers cannot even complain about it. Moreover, accounts are opened in the name of family heads which happen to be men, thus robbing a vast majority of the women workforce of its right over hard-earned money.

Another unsolved issue is making these payment institutions accountable under the MGNREGA as they are guided by their own set of rules. Measures to ensure transparency may be a part of the government’s policy-making exercise; but when it comes to ground reality, it is hard to imagine that these institutions would deliver goods keeping the exigencies of the poor in mind.

Development economist Prof Jean Dreze attributes the delay to the apathy of the implementing officials who take less interest in the timely processing of payments since the new system does not allow for deducting cuts. Apart from this, delay is also caused by the internal processing of payment institutions. This inherent delay occurs as the system is not developed for quick delivery in many states. Overworked and often indifferent bank and PO staffers add to the woes.

Binay Sahu, a grassroots activist in Sundargarh district of Odisha, says, “It has become very difficult to monitor the system and to ascertain at what stage the matters are stuck.”

Local problems need local solutions

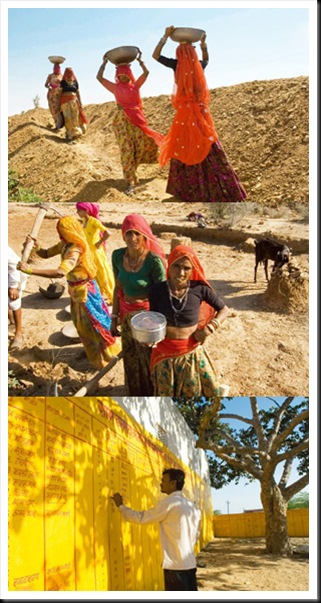

The wage payment monitoring system worked quite well in Andhra Pradesh as the state had designed its own mechanisms, not something imposed from New Delhi, to check corruption. Rajasthan, for example, was also performing fairly well in timely payment of wages and corruption was comparatively low.

In an interface with CSOs at a training programme a year ago, former NRGEA Commissioner Manju Rajpal had said: “we were not in favour of introduction of the bank and post office payment system in NREGA as the direct cash payment system was working well with us. But the Centre made the new system mandatory leaving us no option but adopt it.”

Currently, in states like Rajasthan where the system is performing well in overall implementation of the scheme, delayed payment is not uncommon. Richa of Janchetna Sansthan, Rajasthan, says, “Though the government has already developed the system for proper functioning of wage payment through banks and post offices, it is delayed by two or three months in several cases as the officials pass the buck from one institution to the other.”

The victims’ version

In their article in EPW, Anindita Adhikari and Kartika Bhatia write that about 77% people preferred banks to POs. On the contrary, Tulsa Dharua of Tara village, Belpara block of Balangir district of Odisha, has a different tale to narrate. She has witnessed a starvation death recently and her villagers’ migration to Hyderabad for work. “No matter how we get the payment, if we get our wages in seven days, why would so many people migrate?”

|

Abhimanyu Dharua of Chhuinara village in Balangir district of Odisha says, “The bank payment system is good as the money is not siphoned off. But timely wage payment is very important. In our village, a pond renovation work under MGNREGA was discontinued because of delayed payments. The workers eventually migrated as they did not receive payment on time and the work was stopped. Now I am jobless. When there is no job, where is the scope for corruption?”

Papatu Devi and Koshila Devi from Chhatarpur block of Palamu district in Jharkhand, who have not received payment for their work for the last four months, expressed similar helplessness. Now, people in their village are jobless and the work has been stopped.

In Badbanki GP of Balangir district, 17 families have completed 100 days of employment in the last financial year despite delayed payment. Further inquiry revealed that these families own land and hence can live even without MGNREGA. The work under the scheme comes as an additional source of income for such families. But in the same GP, the poorest lot has migrated as they need immediate payment for their work.

Effects of delayed payment

Loss of trust in the Act is the first casualty. Jawahar Mehta of Vikash Sahayog Kendra, Jharkhand, recounts the situation before a year in Latehar and Khunti districts of Jharkhand, where things had almost come to a standstill due to delayed payment. Neither the administration nor the people took any interest in continuing work under the scheme. “It was only after the intervention by Prof Jean Dreze through his ‘Sahayata Kendras’ did things start moving,” says Mehta.

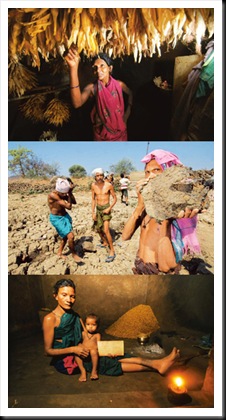

Abhimanyu Dharua of Balangir district of Odisha is now jobless as all the work under the MGNREGA has been stopped in his village due to delayed payment. Pic: Pradeep Baisakh.

People in the undivided Kalahandi-Balangir-Koraput area (KBK region) of Odisha, one of the most backward regions of the country, have resorted to migration as the MGNREGA has almost failed to check distress migration in this region -- initially due to non-availability of work and now, delayed payment.

Contrary to official figures, the MGNREGA is a failed scheme for the needy in Odisha. About 1.5 lakh people from Balangir district alone have migrated this season in search of work. Distress migration figures in the KBK region is somewhere between 8 to 10 lakhs. Starvation deaths in Odisha are going unchecked. In remote areas of Jharkhand, death of women during pregnancy is a cause for concern mainly due to malnourishment and anaemia.

On the other hand, many feel that if loopholes are plugged and strict monitoring measures are followed, cash payment system can work well. Tamilnadu is a case in point. (See ‘Slow but steady success’ by Reetika Khera and Karuna Muthiah in The Hindu on 25 April 2010).

Checking corruption may be a priority for activists, media and the government. But for the poor labourers, ‘aajiki mazdoori, aazka bhoogdaan’ (today’s work and today’s payment) is what counts most. One cannot expect a poor person to fight corruption on an empty stomach. Therefore, the agenda of fighting corruption should follow assurance of regular work and timely payment.

An opportunity to fight feudalism missed?

The MGNREGA was expected to make inroads into the democratic control of design and execution of the government welfare programmes in rural India. By transparent mechanisms like muster roll maintenance and cash disbursement in full public view, designs of community control like choosing work and conducting social audits by gram sabhas had discouraged corruption and also exposed embezzlement by the local elite who controlled local matters. The poorest lot -- labourers, landless, and small and marginal farmers, the potential beneficiaries of MGNREGA -- had even started challenging feudal domination. Maybe, had this trend continued, it could have possibly led to greater social transformation through gradual decimation of feudal dominance.

So long as the cash payment of wages was in place, despite its limitations, it was within the grasp of the common lot and hence, under their control. In such a system, the victims might have not had the courage to question the local elite like sarpanchs, contractors, or the panchayat staff. But in the long run, they could not have tolerated their hard-earned money being bungled up by others.

Though less prone to corruption, the institutional wage payment system cannot be monitored by common people. Thus a noble objective of the MGNREGA lay nullified. It has to be mentioned that corruption in the MGNREGA exposed by social audits was perhaps as bad as it was in other schemes. The only difference was that the strong transparency mechanisms of the Act laid it bare. In all fairness, the government should have persisted with the cash payment of wages and waited for it to show its effectiveness. Unfortunately, it was aborted half way in favour of a system, which, though partially addressed one problem, has given rise to several others.

Poor on the periphery

At policy level, the scenario of delayed payment has improved in states like Jharkhand, Rajasthan, Odisha, etc. These measures have alleviated the problem to a certain extent, though way below expectations. When certain shortcomings of this mode of payment came to the fore, a new system of mobile bank payment through biometric smart card is being experimented in some districts. Though initial observations show good results, only time can tell its real impact.

The concern is: the more the system becomes complicated in vital components like wage payment, the more it drifts away from the common people's understanding. In such cases, the government, social activists, and the media occupy the centre-stage and debate and discuss to sort out the issues. Ironically, the poor stand on the periphery as they have little say on matters that affect them the most.

This is not what the original rozgaar guarantee law envisioned. Just like other welfare schemes which are mostly government-driven, the MGNREGA may end up becoming an activists- or media-driven programme. ⊕

Pradeep Baisakh

17 Jul 2010